Background

- During the

evaluation of Year 1 of Harrow Children’s Fund (HCF), the

issue of safety repeatedly arose. This was linked by a large

number of children in touch with projects to bullying and,

to a lesser extent, to fears of personal violence (attack,

mugging). But, beyond this, several projects described young

people’s appreciation of what they offered in terms of

more general “places of safety”, detached from the

dangers of everyday life. Some went further, to identify

danger in terms of traditional contexts – school, home,

neighbourhood, or relationships – family, community, which

had let children down.

- The

implications of this were discussed by a small steering

group (see Annex A). It seemed to us that the issue of

safety in the broadest sense could be a good focus for

participation by children in the HCF evaluation for a number

of reasons:

1)

It is a genuine concern of children themselves, not a

policy issue imposed on them

2)

At the same time it relates to key local policy concerns,

such as safeguarding children, and crime prevention

3)

Exploring it further could throw light on key issues for

mainstreaming – is part of the value of projects their detachment

from the mainstream? How do we preserve that value, while

ensuring the continuation of the work?

4)

Equally, it may have implications for the extent to which

extended schools can provide the sort of safety children are

looking for, and

5)

It could pinpoint priorities for action by Harrow after

the Programme ends.

- Before

designing our Safety Project, we contacted the (then)

Children’s Rights Director for England, Roger Morgan. In

July 2004, he had published the results of a consultation he

had carried out with 25 groups of children and young people

who had all had experience of living away from their natural

parents.

His findings have been reported in the social work press

with surprise: children in these situations were

concerned about abuse from strangers. But risks in order of

importance were listed as:

1)

bullying

2)

road accidents

3)

illness, and

4)

being abducted.

The

greatest protections against risk were identified as

someone you trust to talk to, and being listened to and taken

seriously – “Listen to the quiet ones too!”

- Although Roger

Morgan’s studies covered a wider age range of children

than ours, and children with a particular experience (of

living away from home), his results provided us with

interesting comparative material. His comments on

methodology – in particular, the need to keep sessions

with the young people flexible and questions open-ended –

were also helpful.

Method

- The methodology

for the project was agreed by HCF’s Management Committee

in September 2004. It was decided that, at the beginning of

the school year 2004-05, all HCF projects would be contacted

for the names of young people interested in becoming part of

the core group of “young researchers” who would firstly

explore the issue of safety together, and then be trained to

survey the views of others using simple checklists

(“Opinion Finders”). At the same time, an expanded

version of the checklist would be posted on the new

Harrowkidz website, and responses would be invited by

everyone visiting the site. A sample of the “Opinion

Finders”, and the website questionnaire are attached as

Annexes B and C.

- The Young

Researchers group (six regular participants aged 9-12) met

throughout the winter for discussion, training and fun. In

January 2005, members of the group were lent digital

cameras, and asked to photograph places, people, anything

which reflected their ideas of what was “safe” or

“unsafe”. A selection of these photos was exhibited in

the Civic Centre. The group carried out their “Opinion

Finders” surveys at school, in holidays and weekends,

interviewing their friends, classmates, and other young

people attending HCF projects. Project providers were also

interviewed in some cases. About 70 responses were collected

in this way.

- The Young

Researchers also attended a 3-day drama workshop in February

2005 on the subject of safety, and created and edited a DVD

– also exhibited at the Civic Centre. Both the DVD and the

photos mentioned above are now being widely used at events

in the borough. The young people were rewarded for their

participation in the 6-month project by a fun celebration

event, and a trip to Thorpe Park.

- The extended

checklist was posted on Harrowkidz website between October

2004 and the present. Forty responses were received by March

2005. Those who stated their age (25%) were between 9 and 13

years old.

Results

- The results

recorded here are derived from participant observation of

the Young Researchers group, and statistical analysis of the

two sets of questionnaire responses. We do not make any

claims about the “scientific” quality of the data: all

participants were in effect self-selected, and the rather

negative feel of some of responses to the website survey may

reinforce the view that it appealed to people with problems,

rather than a random sample of young people. Nonetheless,

the volume of material we collected suggests that the issues

raised are of genuine concern to at least a significant

sub-set of Harrow’s young people. We also cannot be

certain about the age range covered: the likelihood is that

Opinion Finders reflect the views of younger children (up to

13), while the website may have attracted older respondents.

- The results

which follow are broken down into three sections: Young

Researchers, Opinion Finders, and Harrowkidz Website. They

relate simply to the views of young people which were

revealed by the project. An evaluation of the project in

terms of the wider goals of the Children’s Fund will be

covered in the end-year Evaluation Report.

YOUNG RESEARCHERS

- The Young

Researchers (all boys, apart from one girl who attended the

drama workshop) appeared to find it easy to relate to the

subject of the project. Both they (and their parents who

brought them to the sessions) took attendance seriously; and

although each meeting included plenty of fun, the young

people were impressive in the extent to which they were

prepared to discuss and learn at quite long evening

meetings.

- They were

invited to explore and explain their own views about safety

from the very beginning, through a range of activities. It

was impossible for us to disentangle the source of their

views with the resources available to us, but very broadly,

they seemed to fall into three or four categories:

Ø

Fundamental fears and frightening fantasies

experienced by all or most children – of the dark, and dark

places, of being left alone. One of these – fear of kidnap –

which occurred quite frequently, may also relate to stories of

abductions in the press.

Ø

Fears generated by national or world events

reported in the press, involving danger, guns or violence. One

participant, for example, said that beaches were no longer safe.

Ø

Practical concerns for safety instilled by school

and parents: about crossing the road carefully, standing back

from the railway platform edge, paying attention to “hazard”

signs.

Ø

And mixed with all these, many insights into what

it is like to be a young person living in Harrow just now.

- Home and

family, especially Mum, seemed important to all these young

people, and it was clear that their sense of security was

fixed in the familiar. Pluses – things that made them feel

safe – included their siblings, extended family, their

houses, family cars, household objects, holidays, favourite

music, football. A list of “safe” things photographed by

one young researcher included his house, front room, Mum and

friend, and bathroom. He commented that his kitchen, DVDs,

Dad and the garden should also be included! One photographed

his Mum, and said, “ – she’s very nice, comforts and

cheers me up”; while another described his garden as safe

because, “Mum is watching from the kitchen.”

- Perhaps less

predictable were their perceptions of things that are unsafe

in their lives. Important worries included the following:

Kidnapping

has already been mentioned. No-one knew anybody who had been

abducted, but it was generally felt to be a real risk.

Dark

alleyways

A

broad concern with pollution was related to passive

smoking, cars, graffiti, vandalism and rubbish in the streets. Litter

was also mentioned by most, but opinions differed as to how

seriously litter should be treated.

Health

concerns included poor diet, smoking and substance abuse and

alcohol. These young people were against them all.

They

were equally severe about places serving alcohol. Clubs and pubs

that encouraged heavy drinking were associated with

noisy, dangerous gangs; and casinos, with pointless, dangerous

waste of money.

Dangerous

gangs were also mentioned as one of

the hazards of Harrow bus station - again, sometimes in

connection with drugs, alcohol, and mobile ‘phone theft.

Racism

was mentioned as a problem by some, and – conversely – a

“multicultural” setting was seen as a safe one.

- A few issues

were seen as particularly complicated: policing was

one. While the police could be reassuring in some contexts

– for example, outside pubs at night – their obvious

presence in schools was seen as threatening and

heavy-handed. Some held the general view that the “police

will not help you”, even when an obvious crime is being

committed.

- Most saw school

as a fundamentally safe place, and trusted the adults there

to prevent kidnap or other violence. On the other hand,

bullying was generally said to be a problem, although there

had been little personal experience of it.

- As one part of

the preparation for surveying the views of other young

people, the Young Researchers developed their own list of

qualities needed for the task. These were:

Ø

Have confidence – be yourself

Ø

Be polite, truthful, attentive, professional and

mature

Ø

Don’t be afraid, and don’t scare people

Ø

Listen, but have your own ideas

Ø

Make it interesting

Ø

Be prepared – know what you’re going to say

- Overall, the

group thought the project had been very successful. They

said that they had enjoyed learning about what concerned

other people, and thinking about how the environment could

be improved, and young people’s worries about safety

solved. They also said that they had learned a lot about

Harrow, Harrow Council and the Youth Council as a result of

the project.

OPINION FINDERS

- The following

statements are based on the completed or partially-completed

questionnaires (about 70) collected by the young

researchers. Often, the numbers of respondents replying to

any one question are small: proportions which are stated

relate to the number of people responding to the individual

question. Few very young children were contacted: most

respondents would be in the 9-13 age range.

- Relationships

Half the (few) respondents to this question

felt that they could talk to their parents when worried

Virtually

all respondents felt that they felt most safe at home

Seven

out of ten felt that they had someone to turn to when they were

worried; even more, that they have someone they can trust, to

talk to

Virtually

all had an adult to talk to about their problems

- Harrow – the streets and the

environment

Most respondents to this question felt that,

overall, Harrow was a safe place to live

Most

felt that street lighting was an issue – there should be more

Two-thirds

agreed or agreed strongly with the proposition that litter and

graffiti are a problem in Harrow

Virtually

all respondents to this question felt that pollution in Harrow

is dangerous

There

were no strong views about road safety in Harrow

The

majority of a small number of respondents felt that ill-health

was a problem for the borough

- Safe places

All

respondents to this question feel safe at home

Two-thirds

feel that drunks and pubs are a problem in the borough

One-half

believe that racism is an issue

Most

believe strongly that public transport is safe

Two-thirds

feel that the police help them to feel safe

About

half feel that there are safe places to go after school

- School

Three-quarters of the children who answered

this question said that they could always talk to their teacher

when they were worried

More than half feel safe at school

But three out of five think that bullying is a

problem at their school

And more than half think that most children

have been bullied at some time

- Crime

Less

than half of the respondents to this question felt that Harrow

is safer than other parts of London

Most

agreed that there is too much crime in Harrow, and that it is a

problem

But

very few thought that crime was a problem where they lived

Half

knew someone who had been a victim of crime

About

half thought that teenagers could be a problem

HARROWKIDZ WEBSITE

25.

Again, although about 40 responses were collected from

the website up to March 2005, many respondents only answered

those questions of most concern to them.

- Safe places

27 respondents felt safe at home, or at home

with their family; no-one felt unsafe. Others wrote about

supportive friends and family, and feeling safe indoors, when

the family is at home; 3 mentioned feeling unsafe when the

family wasn’t home

Familiar

places and people, lighting, plenty of company, friends,

respected institutions like places of worship or after-school

clubs all inspired confidence, as did traffic control measures.

Locks and dogs were also appreciated.

- Unsafe places

Most unsafe places were “outside”, and 29

people knew of some. They included Harrow bus station, parks and

alleys

Unsafe

places were associated with late night noise and rowdy kids;

drunks; drug use; bullies; crime of all kinds; fights, gangs;

people in hiding, and kidnap

They

also involve physical danger – falling over, falling on

railway lines, traffic

- “I feel safe when...”

“I’m at home, with family and friends, in

a crowd, when the sun is shining, somewhere familiar and in good

lighting”

“When

I’m inside and nice and warm, in bed”

“With

teachers, at school, playing football”

- Things that make me feel unsafe

Bad

language and shouting, people arguing in the street

Strangers, being alone in the house, dark and

lonely streets and alleys, my back garden at night, deserted

places

Fights,

family fights

Gangs

and drunks

- People who are the best protection

against danger

Parents, the wider family and friends were all

mentioned by numerous respondents. Older people could generally

be relied on to help. One commented simply that, “they are all

helpful, but you don’t want them escorting you everywhere”

Teachers/school,

and neighbours were also frequently listed

The

police were listed by six respondents, but had also been listed

as “dangerous” by one

- Bullying

27

respondents were worried about bullying; 7 were not

A

few wrote that it had happened to them: one boy, for example,

was stigmatised for getting on with the girls at his school

But

many respondents knew how it would feel: it made them scared;

they would feel sad, deceived, worried, upset, lonely,

frightened, let down and hurt. Their self-esteem would be

damaged, and it could lead to dangerous violence

Findings

32.

The consistency of the findings across all three samples

is clear. The young people contacted during this project

generally find security within their homes and immediate family,

their neighbours and friends. The only negative points concern

some family fights, being alone at home, and some “dodgy”

neighbours. Neighbourhoods, however, can be dangerous:

alleyways, environmental and industrial dangers can be

compounded – in young minds – by people lying in wait. In

spite of the statistics, crime of all kinds is seen as a

problem. The role of the police is on balance seen as a

positive, but clearly some respondents remain to be convinced

that the police are on their side.

- Poor street lighting, graffiti,

vandalism and rubbish are taken seriously by Harrow’s

young people who identify them with the uncertainty and

social instability which they fear. Drunkenness and loud

crowds around pubs and clubs are almost universally

disliked.

- Schools and teachers receive a

generally very positive response from the young people. But

– in spite of this – school holds one of their chief

fears. Very few seem to have had direct experience of

bullying, but most fear it, and can describe in graphic

terms what it would mean to them.

Conclusion

- This project was to a large extent

experimental. It demonstrated beyond doubt the feasibility,

and the value of involving young people in the evaluation of

social programmes which are of direct concern to their

lives. Our young researchers worked hard and enjoyed the

experience of examining their own lives, and the lives of

their contemporaries in Harrow. They had important things to

say about the streets, schools and homes they experience

every day.

Annex

C: Website questionnaire

1.

Where do you feel safe? What are safe places for you?

2.

Are some places dangerous? In what ways?

3.

When do you feel safe?

4.

What are the things that make you feel unsafe?

5.

Which people are the best protection against danger

·

Family?

– Who exactly...

·

School?

·

Friends?

·

Neighbours?

·

A

particular teacher, or other adult?

6.

What people do you feel really safe with?

7.

Who do you trust, for good advice and support?

8.

Who can you talk to, if you feel worried or frightened?

9.

Does bullying happen/worry you? What’s it like

10.Are

there things about Harrow which make you feel

safe/unsafe?

Roger Morgan (2004) Safe

from Harm: Children’s views on keeping safe,

Commission for Social Care Inspection

From Track Off: www.teachingzone.org/pdf/15-16Phselp.pdf

Railway

crime is a big problem for the people who run the railway tracks

and the trains. It takes place at

railway

stations, on trains and on railway tracks.

At

railway stations, crimes include stealing cars and from cars,

hurting station users or staff, theft from

customers

and damaging station buildings.

On

trains, crimes include stealing peoples’ suitcases, hurting

passengers or train staff and damage by

football

hooligans.

On

railway tracks, crimes include walking on or across the railway

line without using an official crossing,

throwing

things at trains, putting things on the track in front of trains,

dumping rubbish at the side of tracks

and

damaging or spraying graffiti on railway buildings.

These

are some of the shocking facts about railway crime:

•

Half of all damage to trains is usually caused by children between

the ages of 5 and 16 throwing

rocks

or bricks from the side of the tracks or putting things on the

tracks.

•

4 million objects are thrown at trains every year.

•

640,000 objects are put on the tracks in front of trains every

year.

•

It costs the railway industry £260 million every year to repair

damaged trains and tracks,

replace

staff who may have been shocked or injured and in delays to

trains.

•

It is estimated 27 million crimes of going on the railway tracks

without permission (trespass)

are

carried out each year - 17million of these crimes are committed by

adults and 10 million

by

children under the age of 16.

•

It is estimated these crimes of going on the railway tracks

without permission are carried out

by

1 million adults and 1.3 million children under the age of 16.

British

Transport Police is a special police force that deals with all

railway crime.

•

British Transport Police will visit the homes and schools of young

children who carry out acts

of

railway crime.

•

Walking on or near the tracks without permission, except at an

official crossing, is a crime - people can

be

fined up to £1,000.

•

Throwing things at trains is a crime - people can be sent to

prison for life for a serious offence.

•

Putting things on the track that can damage or derail a train is a

crime - people can be sent to prison

for

life for a serious offence.

Going

on or near the railway tracks, either to take a short cut or to

carry out other acts of

railway

crime, is very dangerous.

•

A train cannot stop quickly or swerve like a car. Even a slow

moving freight train cannot stop quickly as it

can

weigh up to 2,000 tonnes.

•

At a speed of 225 kilometres an hour an inter-city train can

travel over 2,000 metres (20 football pitches)

in

7 seconds.

•

If the driver puts on his emergency brakes it would take 2

kilometres for an inter-city train to stop.

•

Track switching points can trap feet causing serious injury or

trap someone in front of a train.

•

Electricity from overhead cables on the railway can ‘jump’

From

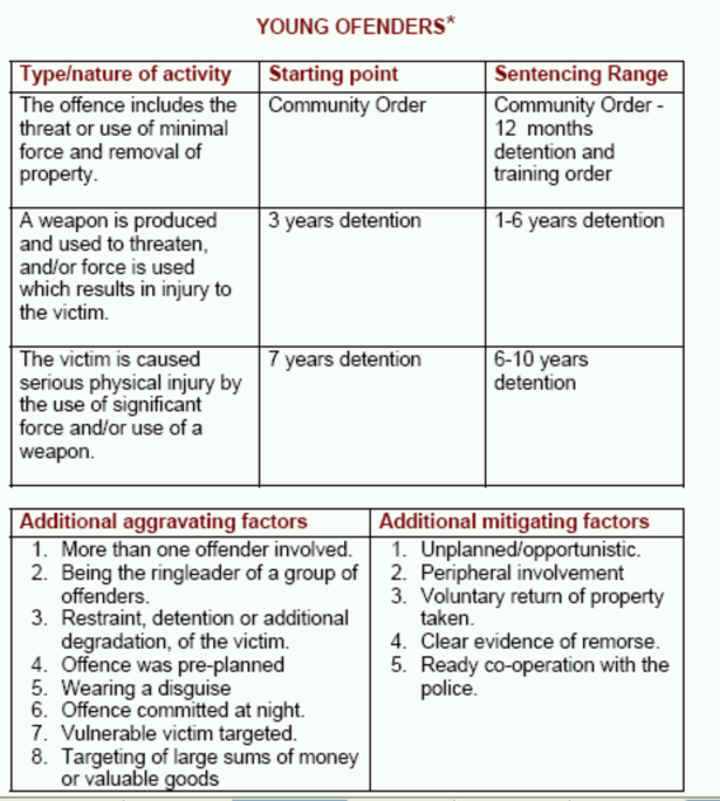

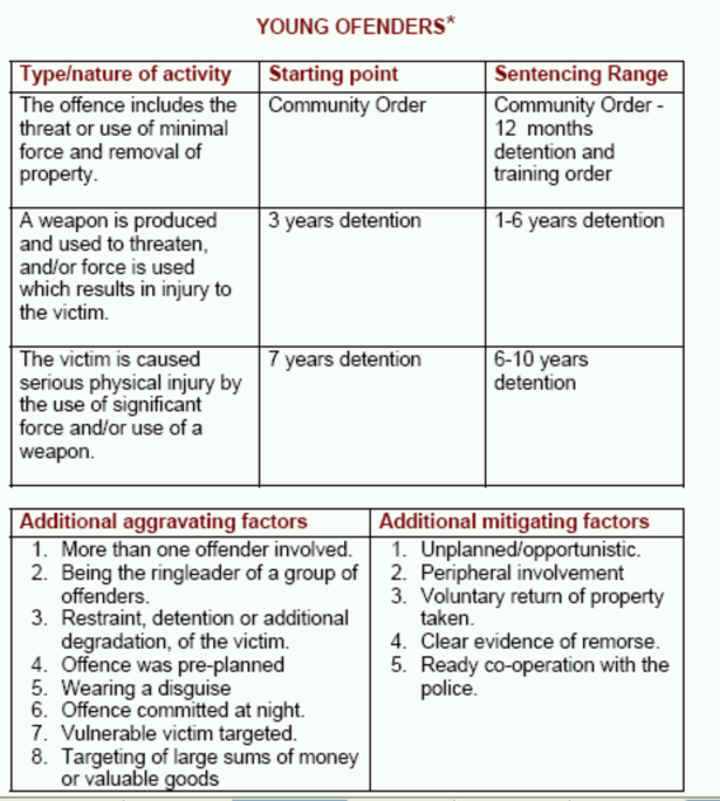

Sentencing Guideline Council Draft Report 2005:

For each of the three categories, three

levels of seriousness have been identified based on the extent of

force used or threatened. For each level of seriousness a

sentencing range and a starting point within that range have been

identified. Adult and youth offenders are distinguished and the

guideline provides for them as separate groups.

How

can I stop the guns?

How

can I stop the guns?

Operation

Trident is the Metropolitan Police's unit which deals with gun related

incidents within London's black community. For more information, go to:

Operation

Trident is the Metropolitan Police's unit which deals with gun related

incidents within London's black community. For more information, go to:  crime

campaign, whose 'Why?' video inspired the Because... youth crime project, go to:

crime

campaign, whose 'Why?' video inspired the Because... youth crime project, go to:

Find

out more at

Find

out more at